Arbiter Case Study

Introduction

Problem Definition

With the rise of remote work and lifestyles, video conferencing has become an indispensable component of modern life1. As a result, it has become a fundamental expectation in many web applications rather than an added benefit.

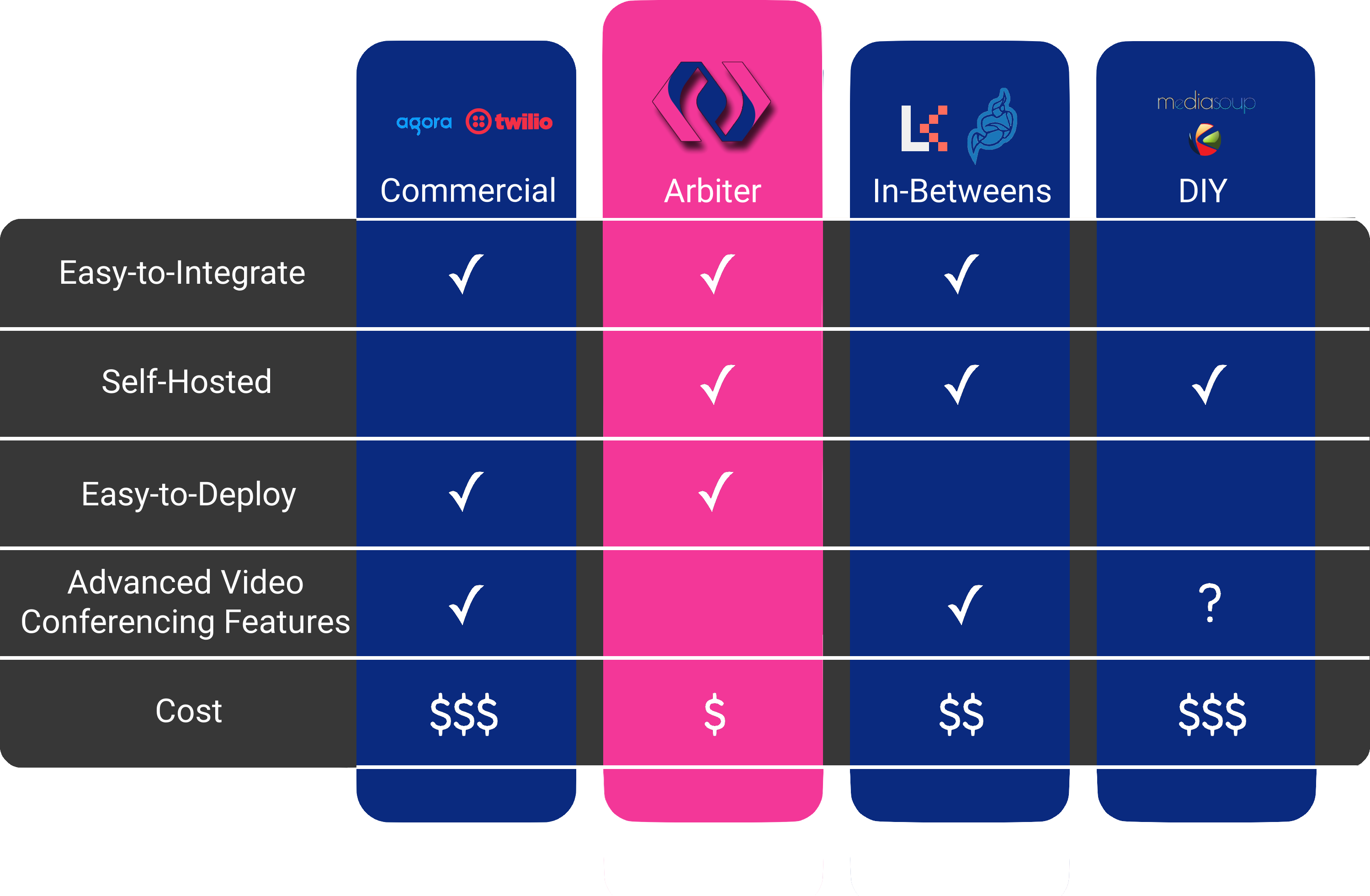

To meet this expectation, developers are increasingly tasked with embedding basic video conferencing capabilities into their web applications, choosing between integrating existing commercial products, developing bespoke DIY solutions in-house, or using an open-source project.

Both commercial products and DIY solutions come with significant tradeoffs. Commercial solutions are often costly2 and lead to dependency on a specific provider, while DIY solutions require substantial developmental resources and specialized domain expertise3. Moreover, while developing a custom solution offers considerable control over the specific features of an application, it diverts attention and resources away from the underlying application’s core functionalities.

To address these problems, we built Arbiter, an easy-to-deploy and open-source video conferencing solution. In this case study, we will examine existing solutions, how we approached the challenges of building a video conferencing framework, and the details of how Arbiter works.

Existing Solutions

As mentioned previously, engineering teams have several options for integrating video conferencing into their applications: utilizing commercial products, developing a custom DIY solution, or leveraging existing open-source projects. The optimal choice depends on multiple factors, including developer availability, budget limitations, and the team’s expertise in media streaming protocols.

Commercial Products

In the domain of video conferencing integration, there are numerous commercial products available. Among the most prominent of these solutions are Twilio4 and Agora5. These companies offer robust Software Development Kits (SDKs), and take on the responsibility of hosting and managing the conferencing features on their own infrastructure.

Opting for a commercial product allows developers to offload the complex tasks of designing and maintaining scalable infrastructure, and the use of SDKs allows for simple integration of video conferencing. These solutions also typically come equipped with advanced features, such as breakout rooms, waiting rooms, and background effects6.

Commercial solutions can be particularly advantageous for well-funded development teams that prefer not to manage their own infrastructure or concern themselves with hosting logistics. However, this route does come with its own set of challenges, most notably cost, lack of control over infrastructure, and vendor lock-in.

DIY

Alternatively, a development team might consider building their own video conferencing solution using basic open-source libraries. Among the notable open-source projects in this space are mediasoup7, and Kurento8. These projects offer low-level implementations of web conferencing protocols. However, it’s important to note that these open-source libraries do not provide hosting solutions or server logic. This means that the onus of designing and deploying both application logic as well as a scalable cloud architecture falls squarely on the development team. As a result, integrating video conferencing in this manner could lead to a slower time to market and a significantly greater development effort when compared to other options.

In-Betweens

As an alternative to commercial products or DIY, there exists a middle ground approach. This middle ground option encompasses a variety of open-source frameworks, which can provide a means to integrate video conferencing capabilities into an application. These projects offer out-of-the-box video conferencing capabilities and Software Development Kits (SDKs), but stop short of providing hosting or specific self-hosting guidelines.

Unlike purchasing a commercial product, opting for an open-source project can be more cost-effective as there are no upfront costs. That said, this path demands cloud hosting expertise as well as domain knowledge to connect the pieces of infrastructure correctly.

Among the open-source solutions available, LiveKit9 and Jitsi Meet10 stand out due to their robustness. These solutions are similar to commercial offerings in terms of advanced features and the customizability of their APIs and SDKs. However, deploying and maintaining these projects is a more involved process due to the absence of managed infrastructure.

Despite these tradeoffs, leveraging an open-source project might be a viable option for teams that possess the necessary expertise and time to design and manage their own infrastructure. This route offers advanced capabilities and control, without the recurring costs inherent to commercial products.

Introducing Arbiter

To bridge the gap between the existing commercial offerings and DIY video conferencing solutions, we have developed Arbiter. Arbiter is a cloud-native framework designed specifically for integrating video conferencing within existing web applications and can be deployed to Amazon Web Services (AWS) with a single command. Arbiter is tailored for development teams that need a straightforward solution to support real-time conferencing for many users across numerous rooms. Arbiter also simplifies self-hosting by abstracting the complexities involved in designing and deploying a scalable cloud infrastructure.

Arbiter’s unique approach to this problem addresses the major trade-offs between commercial products and fully-featured open-source solutions. Arbiter offers automated cloud deployment that enables development teams to integrate video conferencing into their applications quickly and with minimal complexity. By using Arbiter, teams can avoid the extensive time and effort typically required for developing and deploying video conferencing features, while still retaining the advantages of owning their infrastructure. In order to address the gap in existing solutions, we aimed to engineer a product embodying several essential characteristics:

- Near real-time audio and video streaming capabilities

- The capacity to support multi-user calls across numerous rooms

- Seamless integration with pre-existing applications

- Simplified self-hosting

In subsequent sections, we will delve into the methodologies employed to realize these features, along with discussing the trade-offs and challenges encountered during the development of Arbiter.

Fundamental Considerations Building Arbiter

Choosing a Media Streaming Protocol

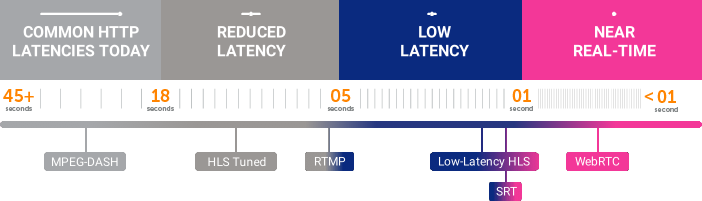

In order to create an application with real-time audio and video streaming, one of our primary considerations was the selection of an appropriate media streaming protocol. The landscape of media streaming protocols is diverse, each presenting its own set of trade-offs in terms of device and browser support, ease of integration, compatibility, speed, and security, among other factors. Some of the commonly used protocols in streaming media include11:

- HTTP Live Streaming (HLS)

- Dynamic Adaptive Streaming over HTTP (DASH)

- Real-Time Messaging Protocol (RTMP)

- Secure Reliable Transport (SRT)

- Web Real-Time Communication (WebRTC).

In our evaluation, WebRTC emerged as the most suitable protocol for several critical reasons:

- Its low latency, which is paramount in video conferencing for near real-time interaction.

- Its wide browser support, enabling applications to run seamlessly across major web browsers without additional software downloads.

- Its robust end-to-end encryption, which ensures privacy and security by encrypting data using the Secure Real-time Transport Protocol (SRTP).

While WebRTC has significant advantages12, it is a relatively new protocol that has certain limitations. For instance, though WebRTC ensures end-to-end encryption, it compromises some degree of application control over user media streams. Additionally, WebRTC does not yet match the extensive device compatibility and adoption levels seen in protocols such as HLS13.

Despite these limitations, we decided to utilize WebRTC for Arbiter's development, primarily due to its alignment with our objectives of seamless integration and real-time video conferencing. It is crucial to acknowledge, however, that WebRTC, despite its numerous advantages, is a sophisticated browser specification and suite of protocols. Implementing it successfully requires a deep understanding of its intricacies.

What is WebRTC?

WebRTC is an open-source specification that enables two peers to establish a connection in order to facilitate real-time communication. This specification details the protocols and methods necessary for sending and receiving media, like ICE (Interactive Connectivity Establishment) and SDP (Session Description Protocol), which are fundamental in establishing and maintaining connections.14

One of the key characteristics of WebRTC is its use of the User Datagram Protocol (UDP) in place of the more traditional Transmission Control Protocol (TCP). UDP is particularly advantageous for video conferencing applications where low latency is imperative because it does not require the establishment of a connection before data transfer and does not implement error correction mechanisms like retransmission of lost packets, which can significantly reduce delays in communication. The preference for UDP, despite the potential for packet loss, underscores the priority of maintaining real-time communication with minimal delay15.

How WebRTC Works

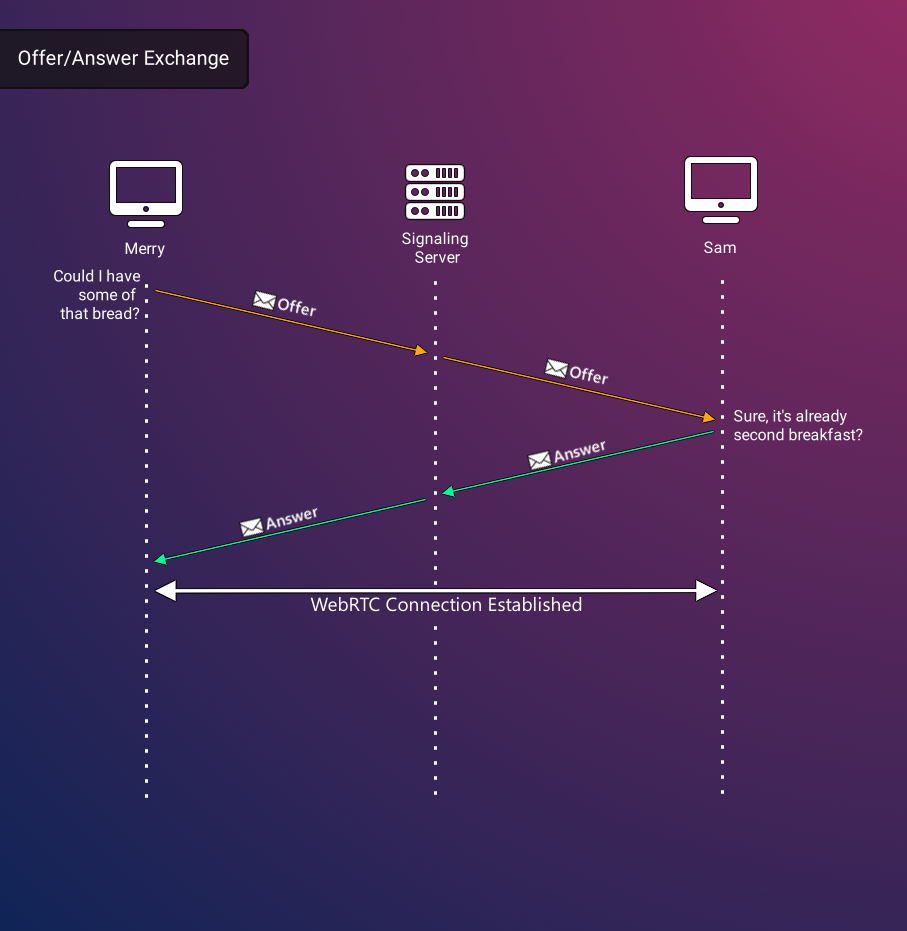

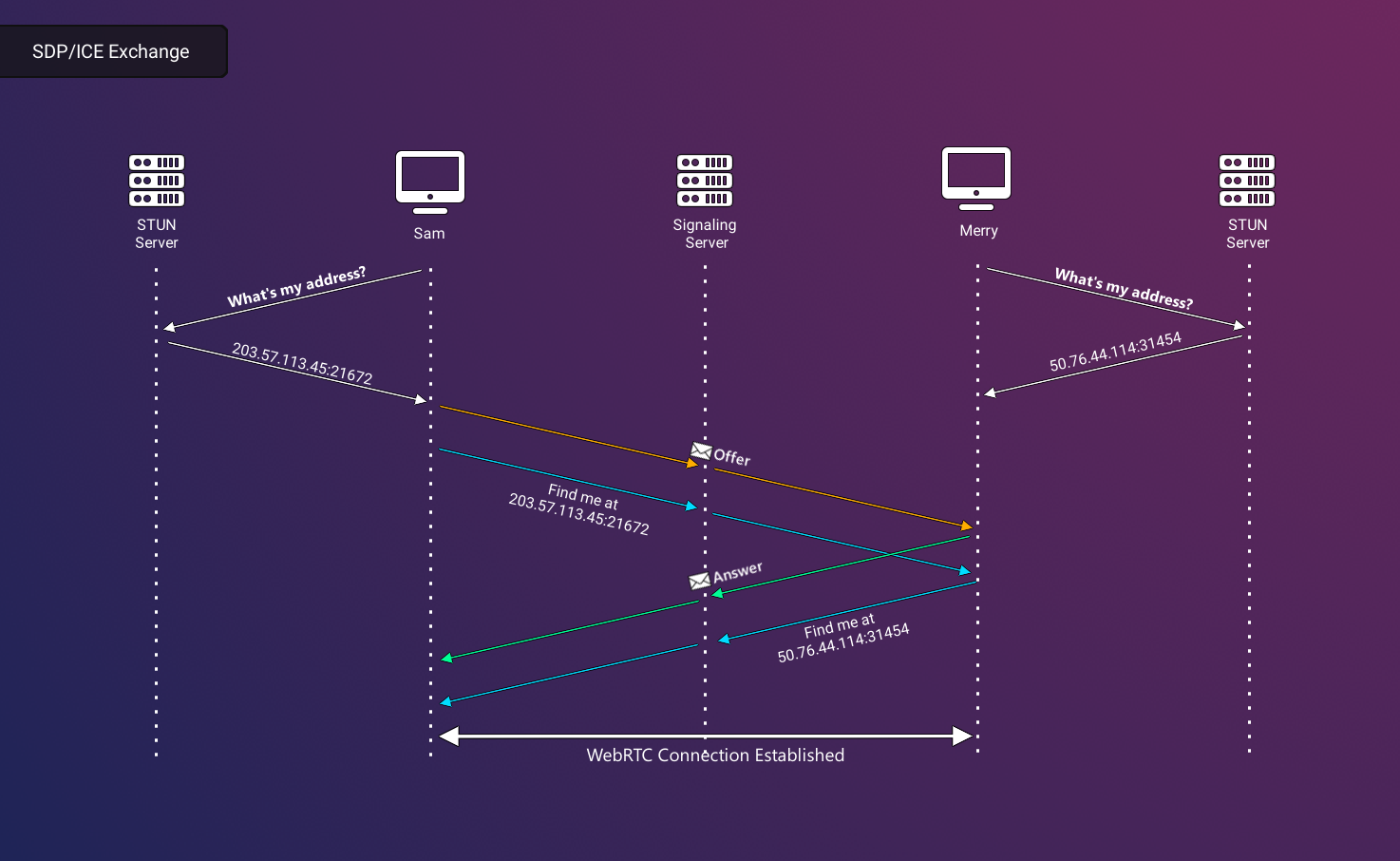

With WebRTC, establishing audio and video communication between computers involves a nuanced, multi-step handshake process called negotiation that is reliant on the specialized protocols ICE and SDP. The negotiation process is only possible after the peers have a clear understanding of how to connect with each other16.

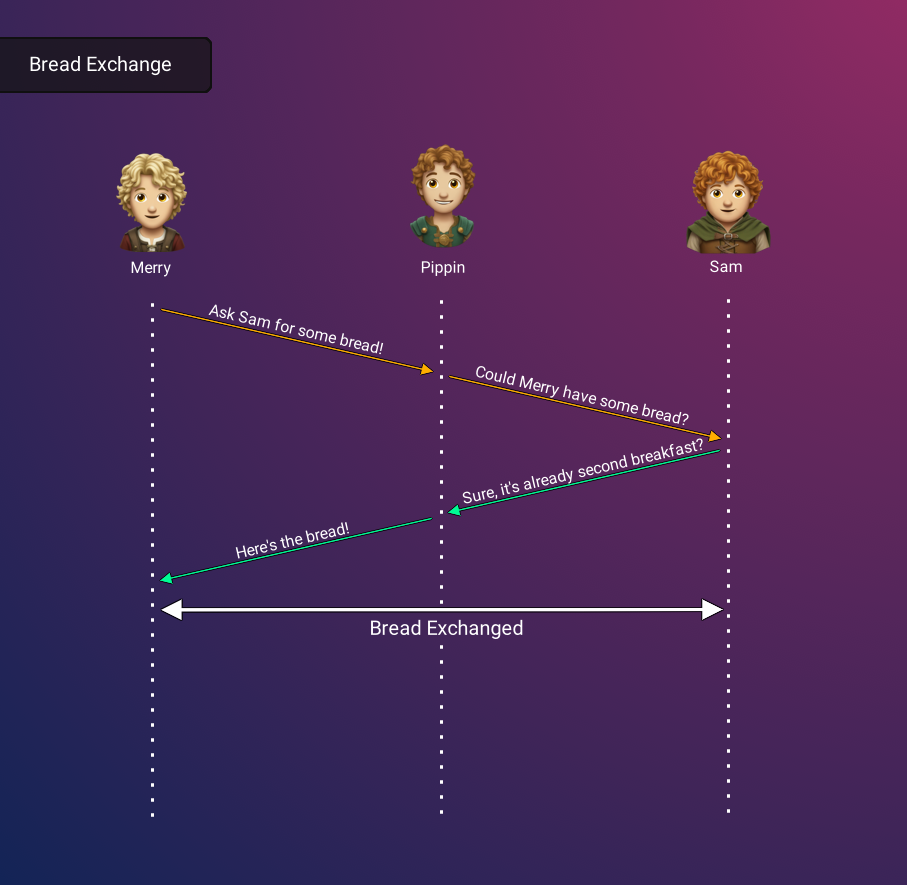

In order to understand the nuances involved in setting up a WebRTC connection, let's consider a real-world scenario. Imagine Merry is in urgent need of bread and seeks to coordinate with Sam to obtain some. However, Merry lacks information about Sam's whereabouts and the appropriate time for a meeting. Consequently, Merry turns to an intermediary, Pippin, who possesses the requisite knowledge to locate Sam and communicate Merry's availability for a rendezvous. This enables them to effectively plan the discussion about exchanging bread.

Pippin's role in the above scenario symbolizes a pivotal step in the formulation of a WebRTC connection, termed 'signaling'. This phase involves peers determining their strategy for connection, thereby establishing the groundwork for subsequent communication. Notably, it is imperative that this signaling phase is concluded successfully for WebRTC connection to be established.

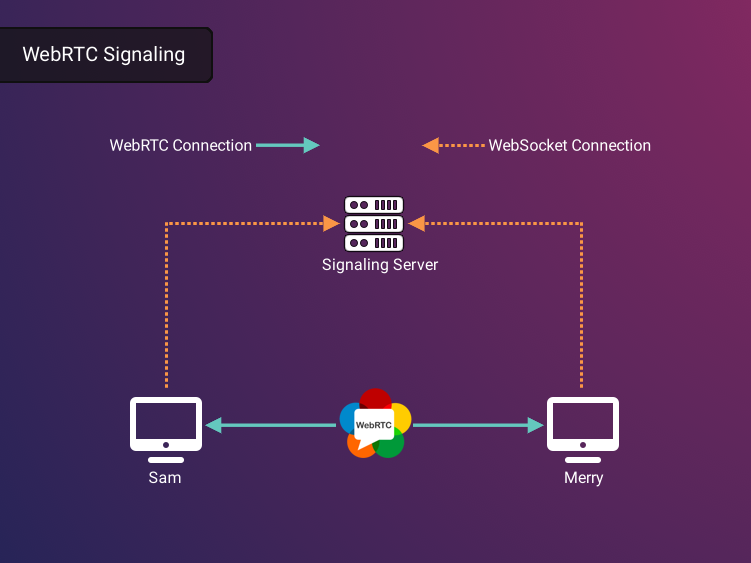

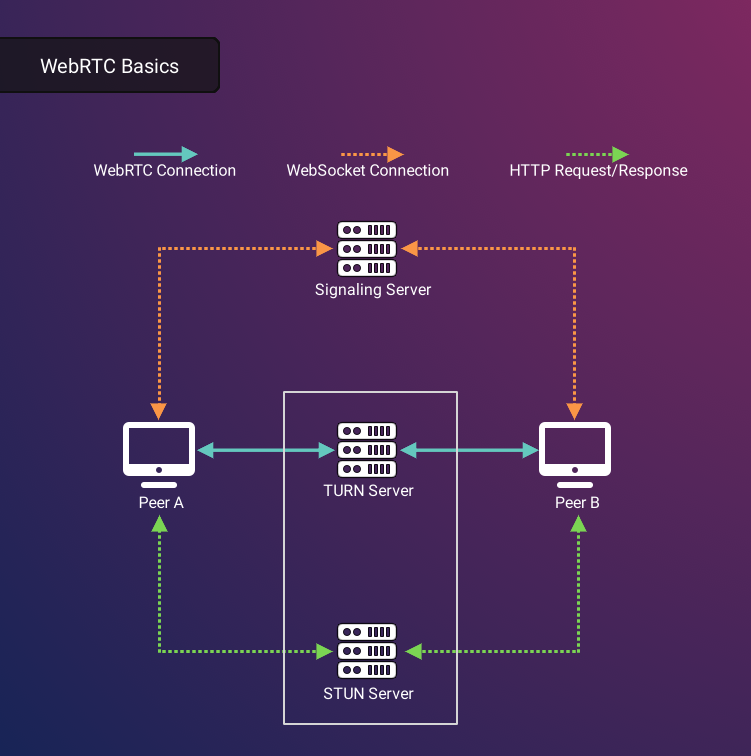

Signaling Servers

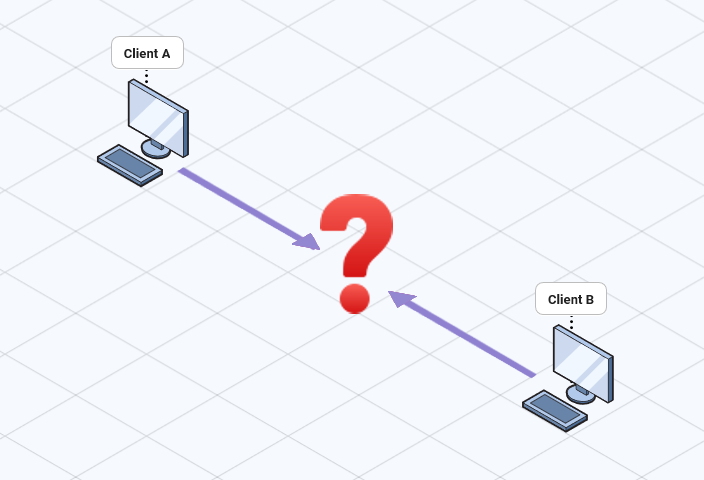

During the initial signaling phase of establishing a WebRTC connection, computers will need to share several key pieces of information. At its core, WebRTC establishes a direct, peer-to-peer connection, and therefore, having detailed information about the peer with which a connection will be established is necessary. Specifically, peers need to know the IP address and Session Description Protocols (SDPs17) to allow peers to know where to find each other, as well as what types of media to expect. The mechanism by which computers share this peer information is called a signaling server.

Let’s return to Sam and Merry to illustrate the purpose of the signaling server. Instead of exchanging bread, imagine that Sam and Merry want to engage in a video conference using WebRTC. For Merry to initiate this connection, he first needs to offer to connect to Sam. However, without an existing connection or specific knowledge of Sam’s IP address, they must both rely on an intermediary they can trust to create a direct connection. In the previous example this was their friend Pippin, but in WebRTC, this is a signaling server. Like Pippin relaying where and when to meet, this server acts as a messenger, transmitting messages back and forth to exchange location and media streaming information, thereby laying the groundwork for data sharing.

Because both peers are connected to the same intermediary server, Sam can send a message to the signaling server, which is then relayed to Merry. In response, Merry can communicate back through the server.

While the advantages of using WebRTC are clear, there are a few roadblocks that need to be overcome to establish direct connections. A primary challenge arises from the widespread use of Network Address Translation (NAT) devices. These devices, while crucial for conserving IP addresses, obscure the actual IP addresses of computers, making direct connections tricky.

STUN/TURN Servers

What is NAT and why is it a network obstacle?

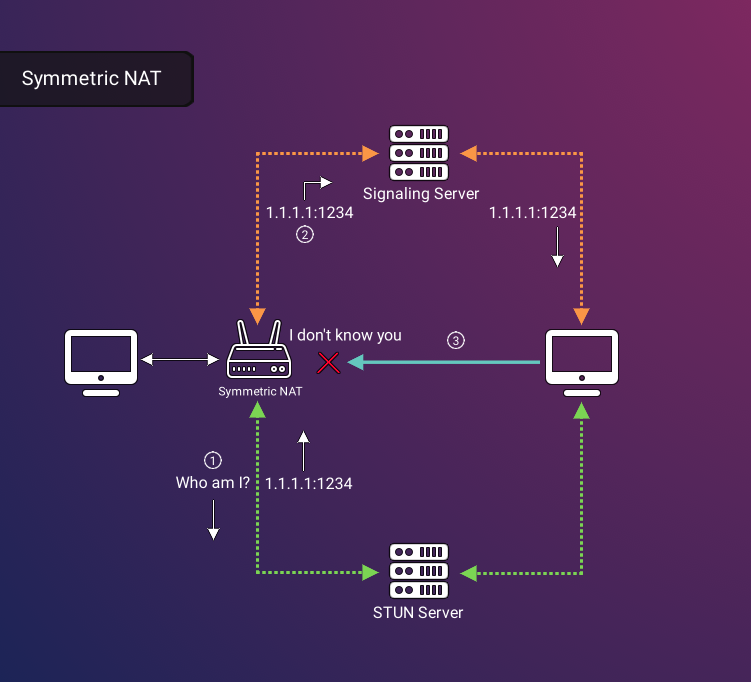

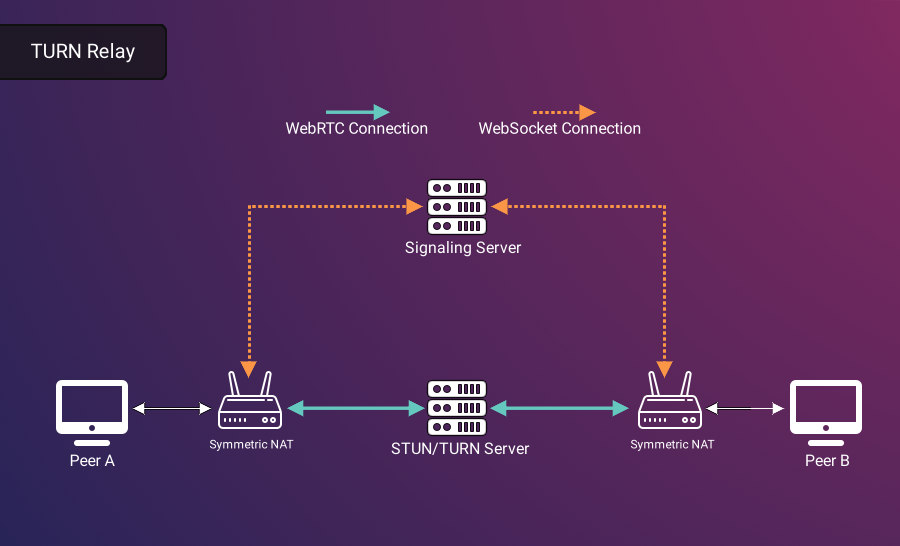

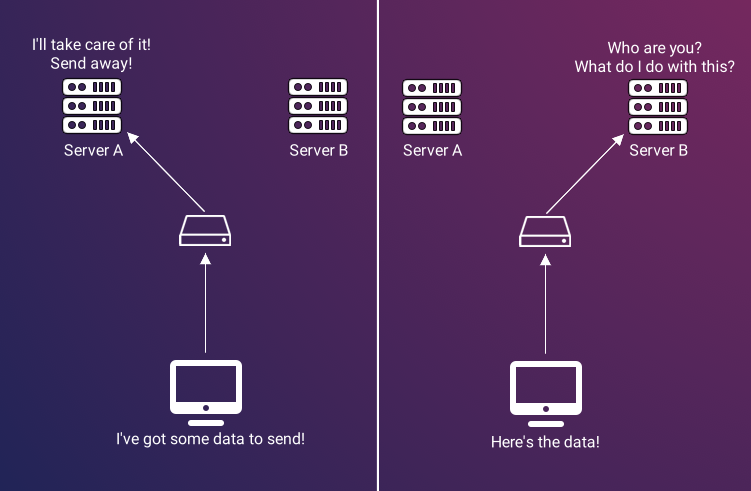

The need for NAT devices stemmed from the limitations of the IPv4 p90 90 90 90 90RTC connection. First, computers behind a NAT device are unaware of their public IP address and port used by the NAT device, which are necessary for negotiating WebRTC connections. Secondly, certain NAT configurations, like Symmetric NAT, restrict direct WebRTC peer connections due to their security settings.

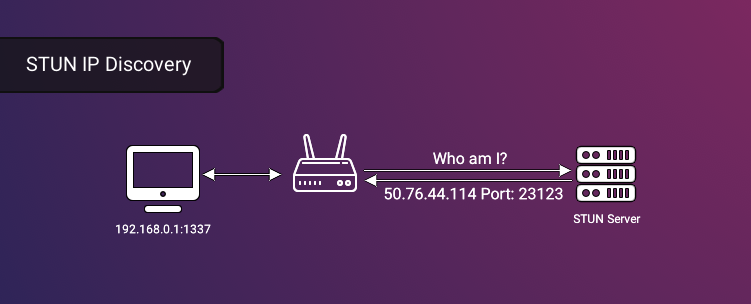

What is STUN?

Addressing the first challenge, the STUN protocol, or Session Traversal Utilities for NAT (RFC 8489 18), enables a device behind a NAT to discover its public IP and port. The process involves sending a request to a STUN server, which then informs the device of its public IP address so that it can offer this information to other computers that want to connect with it directly.

However, there are NAT configurations like Symmetric NAT where even STUN encounters limitations19. In a Symmetric NAT setup, the NAT device assigns a distinct IP address and port combination for each outgoing traffic session. Consequently, when a STUN server responds to a computer seeking to establish a WebRTC connection, it provides an IP address and port combination that is specific to the communication with that STUN server alone. If another computer - in this case the WebRTC peer - attempts to use that address to connect, it will fail because it did not provide that specific IP-port combination that was uniquely assigned to the original STUN communication.

As an analogy, this situation is akin to a customer being advised to enter a store through the shipping dock when inquiring about access. While technically a point of entry, the shipping dock isn’t the appropriate or intended access point for a customer.

Just like a customer being turned away from a shipping dock, a WebRTC peer trying to connect using an incorrect address will encounter a barrier. This results in the inability to establish a direct connection. In such cases, the necessity of a relay between the users becomes apparent, bridging the gap created by these network configuration challenges.

What is TURN?

When a client has a restrictive security configuration - like with a Symmetric NAT - the Traversal Using Relays around NAT (TURN) protocol (RFC 8656 20) can be used by a server to relay that peer’s media streams. In essence, a TURN server acts as a peer to which a client can connect, and the TURN server establishes another connection with the peer originally intended. Notably, this requires a TURN server to use a lot of bandwidth and computational resources because it may need to forward the media streams of many clients.

Establishing a Connection

Given the need for signaling and IP-related issues, a WebRTC-based video conferencing application must incorporate both a signaling server and a STUN/TURN server to facilitate NAT traversal. These servers form the backbone of a WebRTC application, enabling the seamless and secure exchange of real-time audio and video data across the web.

Once a signaling server and STUN/TURN servers are in place, a WebRTC connection can be established using a series of distinct steps.

- Creating an offer to connect

- Accepting that offer

- Exchanging Interactive Connectivity Establishment (ICE) Candidates

While these steps represent a high-level overview of the process required to establish a WebRTC connection, there are several important details to note during this process.

First, in the creation or acceptance of an offer, a client must define its Session Description Protocol (SDP). The SDP details the specifics of the connection, including the client’s capabilities and the particular features it intends to share.

Second, ICE candidates represent potential ways through which clients can connect to one another directly21. The information returned by STUN/TURN is used by the client to generate ICE candidates that can be potential public IP addresses, or relay servers via which an indirect connection can be established.

A signaling server is vital to this process because it serves as the conduit through which ICE candidates, SDPs, and other essential pieces of information are exchanged between clients.

Selecting a Topology

Subsequent to integrating signaling and STUN/TURN servers, a significant factor in the development of Arbiter was meeting our goal of accommodating numerous users across various rooms. Addressing this objective necessitated an evaluation of the constraints posed by a Peer-to-Peer (P2P) mesh topology, which is intrinsic to the WebRTC's specification.

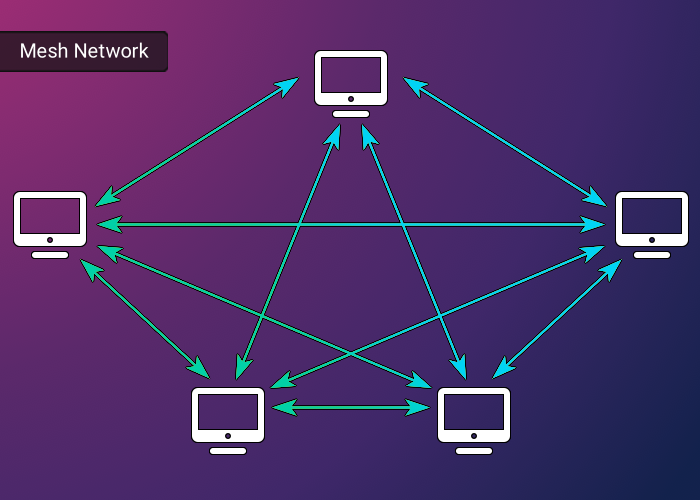

Mesh

A mesh topology is characterized by a network architecture where each client is connected directly to every other client. In the context of WebRTC, this translates to each participant maintaining a direct WebRTC connection with all other participants. The result is a configuration where each client sends its media streams to all other clients, creating ‘n - 1’ outbound connections, and similarly, receives a stream from each of the others, amounting to ‘n - 1’ inbound connections.

While a mesh topology offers some advantages like a simplified infrastructure and lower costs due to the absence of a central server, it comes with significant limitations22. The requirement for each client to manage many connections means that the feasibility of this topology diminishes rapidly as the number of participants increases. It becomes constrained by the bandwidth and processing capabilities of each client’s computer, making it suitable primarily for small-scale video streaming applications. Indeed, our testing found that sustaining a call with more than three participants was challenging, with the call’s integrity degrading beyond this number.

Client-Server

To address this shortcoming, we considered the use of a client-server topology in order to reduce the resource demand on individual clients. With less demand on clients, Arbiter would be able to sustain a larger number of clients simultaneously, which better fulfills Arbiter’s main goals.

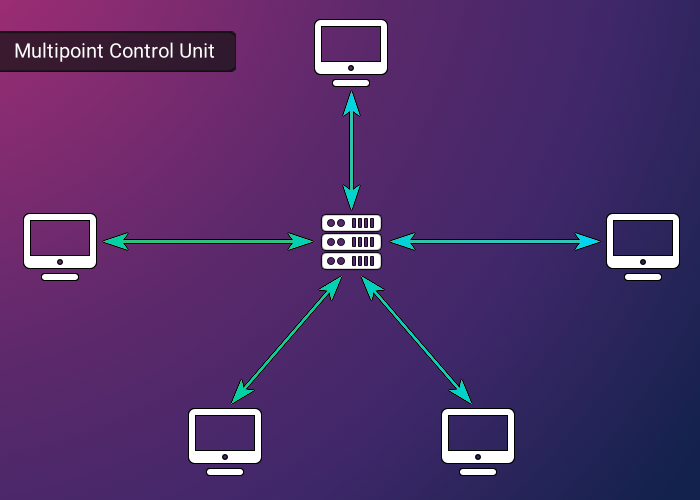

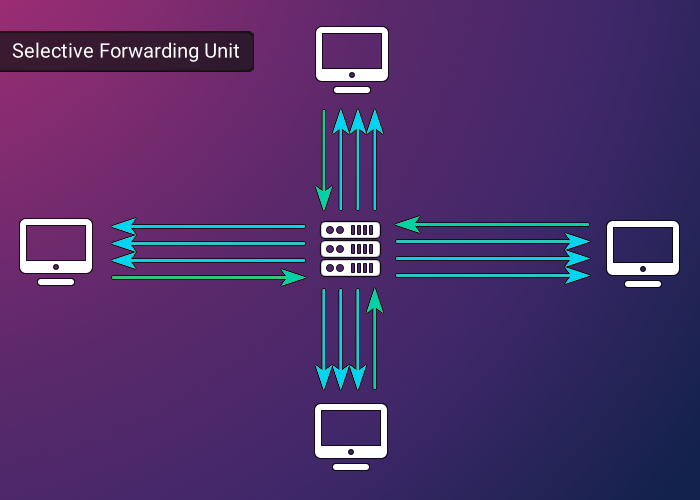

Practically, there are two main WebRTC client-server topologies: using a Multipoint Control Unit (MCU) or a Selective Forwarding Unit (SFU)23. These specific topologies appear similar, but are distinguished by the nature of the connection between client and server. Both the MCU and SFU topologies present distinct trade-offs in the context of WebRTC-based communication.

In an MCU topology, the Multipoint Control Unit acts as a central server. It amalgamates all incoming client streams into a singular stream and then redistributes this combined stream to each client. The key advantage of this approach is that each client is required to maintain only one WebRTC connection with the MCU server. While this significantly reduces the bandwidth and processing load on each client, this centralization means that the MCU server itself must shoulder a heavy computational load to process all incoming user data.

Compared with an MCU, an SFU topology involves a server that also receives streams from all clients but differs in its approach to redistribution. Similar to an MCU, this alleviates a lot of the burden on each client. However, while an MCU reduces the number of connections to 1, an SFU topology still requires each client to receive ‘n - 1’ connections from the SFU. This hybrid approach increases the burden on each client, but also allows for a significantly reduced computational burden on the server.

While both an MCU and an SFU topology offer distinct benefits, Arbiter employs an SFU topology for several key reasons:

- Using an SFU server topology is much more cost-effective with our cloud-based hosting strategy because processing power on AWS is more expensive than multiple server instances.

- By forwarding streams without mixing, we preserve the end-to-end security inherent in WebRTC.

- As the SFU server does not process the streams, it maintains the low latency that WebRTC is renowned for, ensuring a seamless communication experience.

Prototyping Arbiter

Designing a Selective Forwarding Unit

After determining that a Selective Forwarding Unit (SFU) topology most closely aligns with Arbiter’s use case, we sought to design and build an SFU. This solution would allow us to accommodate an increased number of peers in a single call, while also streamlining the connection establishment process.

The most significant challenge in the development of Arbiter was the scarcity of detailed resources on constructing an SFU. Extensive research through commercial offerings, open-source projects, articles, and WebRTC literature revealed the implementation of an SFU as largely opaque.

The absence of detailed literature or existing models left a gap in our understanding of the technical implementation of stream forwarding. Consequently, our approach involved the development of basic prototypes, aiming to resolve these challenges based predominantly on our understanding of the WebRTC specification.

The initial prototype was rudimentary, and merely took the media streams from one user and added them to another user’s existing connection. However, this method had notable drawbacks. For instance, adding a media stream to a WebRTC connection initiates a renegotiation process, disrupting the call each time a new user joins. The capacity of media streams per connection was ambiguous, and browser limitations on video tracks further complicated the scenario. Additionally, the process of disconnecting users from the stream required intricate logic to manage connection identities.

Subsequently, we delved into codebases of existing open-source SFUs, eventually designing our implementation around a producer-consumer model. This approach involves establishing a distinct WebRTC connection for each user (producer connection) and creating additional consumer connections to all other users for stream forwarding. This method simplifies the process without complicating existing connections.

For example, if Sam is the sole participant in a call, the SFU creates a single producer connection. Upon Merry joining the call, the SFU establishes a new producer connection for him and consumer connections for each priorly connected peer (just Sam in this case). Finally, Merry will have a new connection created for each existing producer (still just Sam) established with him as well.

The procedure repeats with each new participant. When Pippin joins Sam and Merry’s call and has his producer connection established, new consumer connections are first created for Sam and Merry. Then, Pippin receives consumer connections for both

Ultimately, this solution requires that the SFU create ‘n’ peer consumer connections (where ‘n’ represents the number of connected peers), and ‘n * (n - 1)’ consumer connections with each peer. Fundamentally, this complexity imposes considerable demands on the SFU’s underlying hardware, emphasizing the need for robust system capabilities. Additionally, we identified opportunities to refine and optimize the signaling logic, leveraging the asymmetric dynamics of the client-SFU connection.

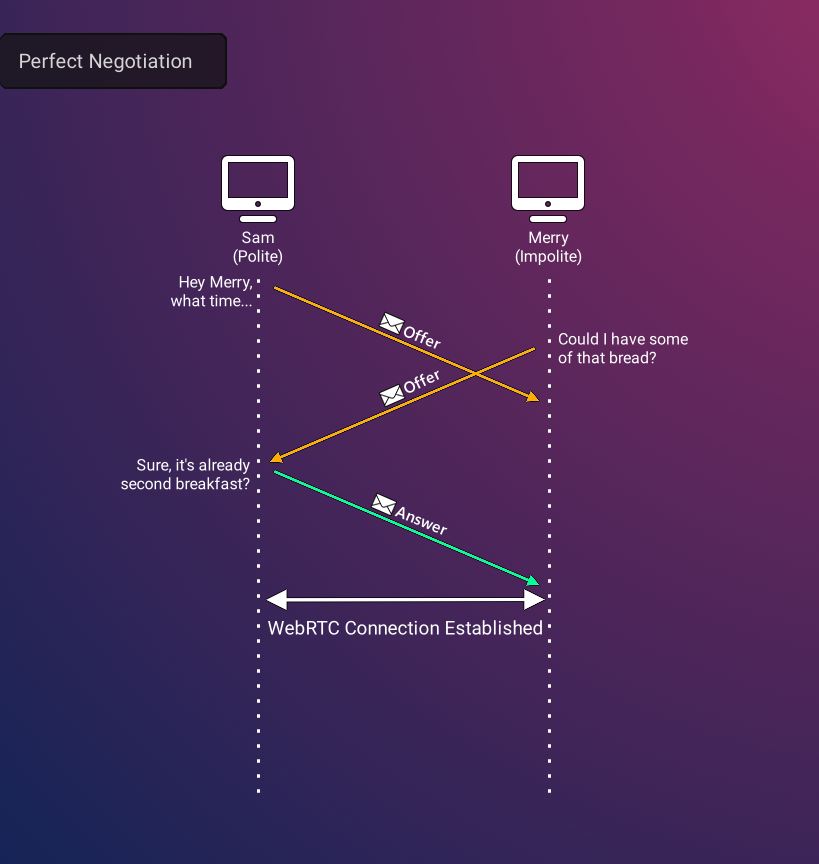

Implementing Signals

The necessity of SFU negotiation of many producer and consumer connections can present significant challenges due to its inherently complex specification. This process involves extensive exchange and verification of information between peers prior to establishing a WebRTC connection, often leading to intricate logic and complications in handling edge cases. Generally, P2P WebRTC applications employ Perfect Negotiation24, which is a strategy in which one peer is predictably ‘polite’ in order to avoid errors when both parties attempt to initiate negotiation.

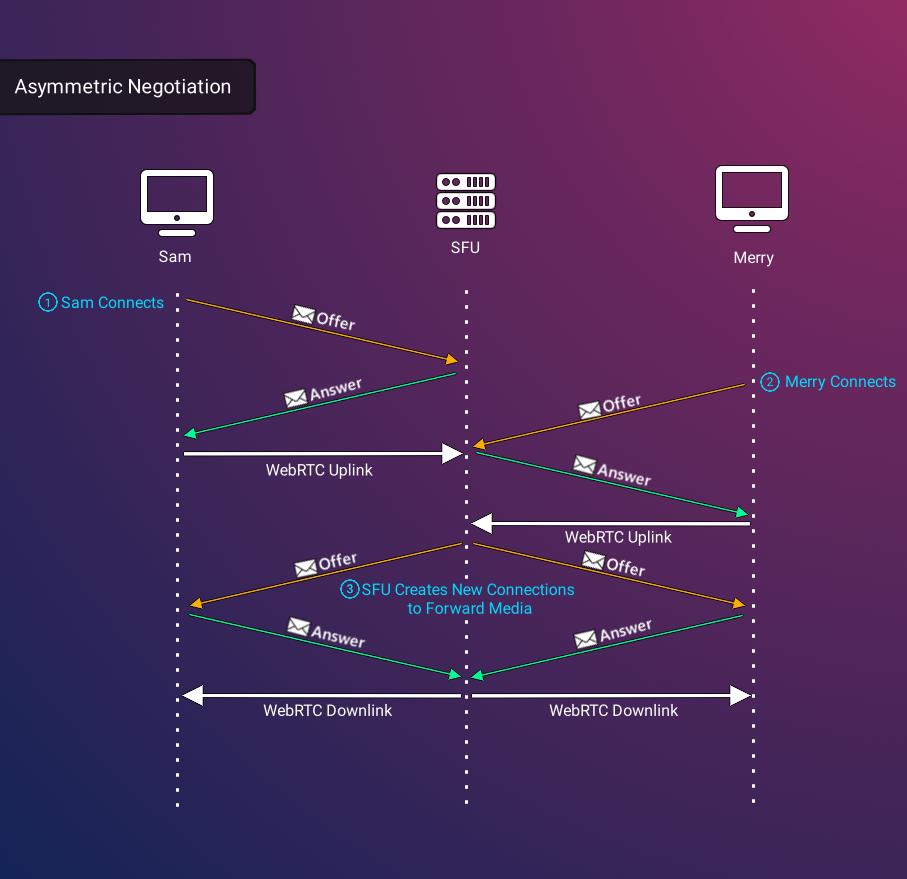

However, using a central server for negotiation creates an additional layer of negotiation complexity. The order in which peers send and receive streams to and from the SFU is determined by other users in the call, which can lead to extremely complex handshake logic. In order to avoid these complexities, we devised a predictable pattern of negotiation that we call Asymmetric Negotiation, in which the party making an offer to connect changes depending on what type of connection needs to be established. For producer connections, the client invariably initiates the connection with the SFU. Conversely, the SFU initiates the connection for new consumer connections because it is the first entity aware of the need for a new connection. This simplified logic achieves a predictable negotiation pattern for establishing WebRTC connections when new peers join.

Prototype Shortcomings

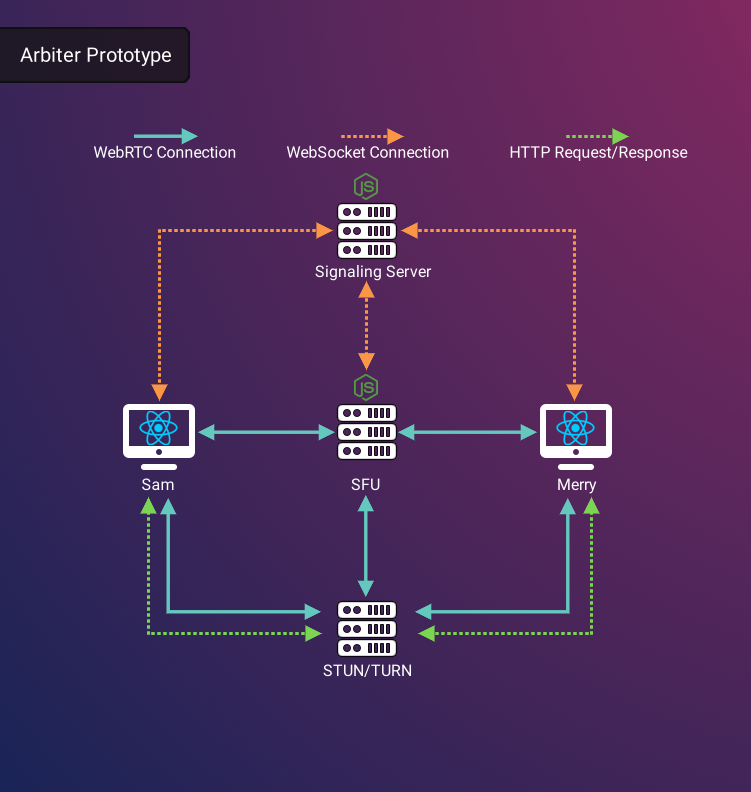

Despite the challenges that we resolved when prototyping Arbiter, we also noted some serious shortcomings in our initial architecture and design. Although the prototype effectively achieved real-time conferencing and supported calls with multiple users, it fell short in facilitating numerous rooms, effortless integration, and self-hosting capabilities.The Arbiter prototype consisted of a Node.js SFU, a Node.js Express server using websockets for signaling, and a simple React application as a client. While this configuration achieved Arbiter’s goal of allowing for video conferencing with many users, this model proved difficult to scale. To fully realize Arbiter's objectives, it's imperative that each component is designed for easy cloud deployment and scalable to accommodate varying demands.

Arbiter’s inability to scale clearly highlighted a fundamental issue with our infrastructure, which was hosted on AWS Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2). WebRTC-based video conferencing is fairly resource-intensive, and testing made it clear that each room would need its own SFU server instance in order to accommodate a larger number of clients. Due to the fact that deploying, configuring, and initializing a single EC2 instance is a complex and time-consuming process25, we needed to find a simpler way to provision new SFU servers in order to increase the number of rooms. Our STUN/TURN server was also hosted on EC2, which would create the same scaling challenges as the SFU rooms. TURN acts as a media relay, meaning that many users using the same TURN server can overwhelm that server. Therefore, more users using TURN will require more instances of TURN servers.

Similarly, we concluded that hosting our signaling server on a persistent EC2 server would be inefficient and costly26. Signaling is almost entirely utilized at the start of a call in order to establish connections between WebRTC peers. Thus, having a permanent signaling server could potentially lead to unnecessary resource consumption and scalability challenges, particularly in high-load scenarios.

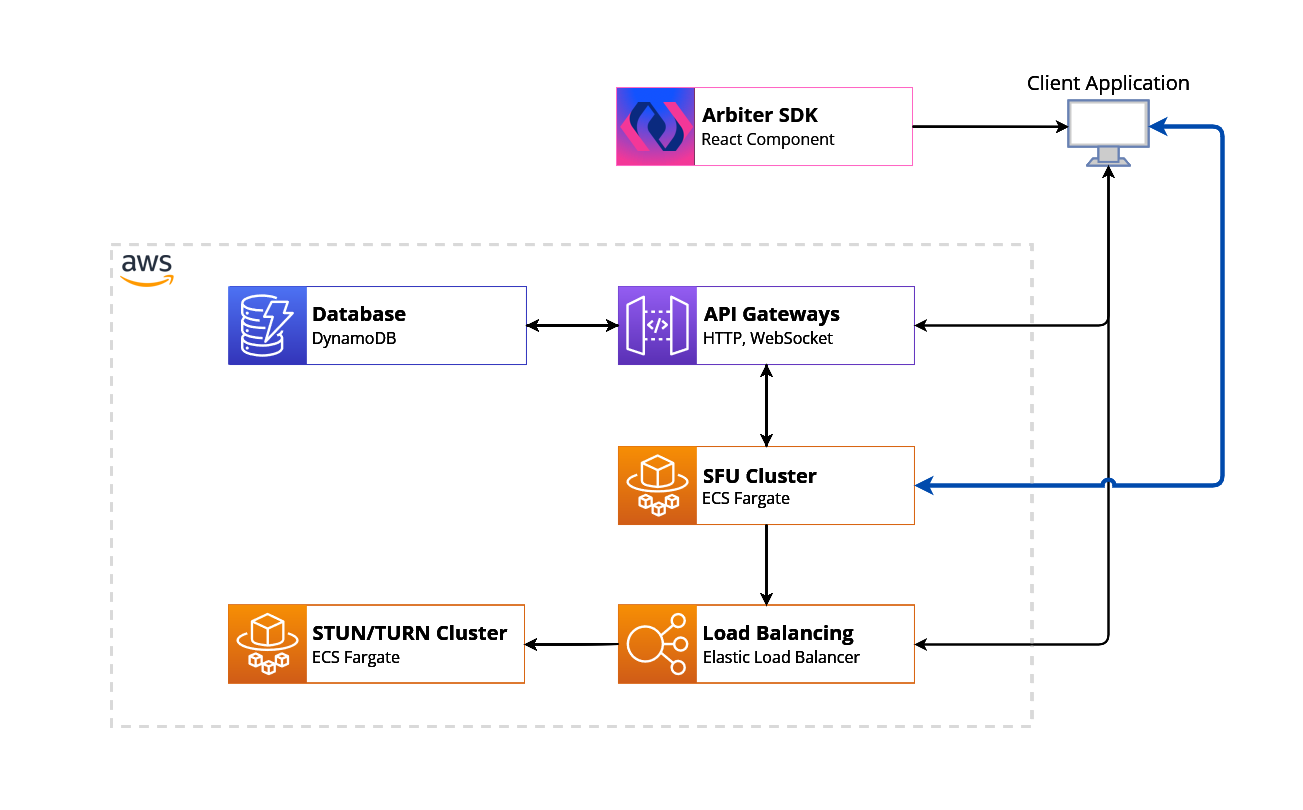

Redesigning Arbiter

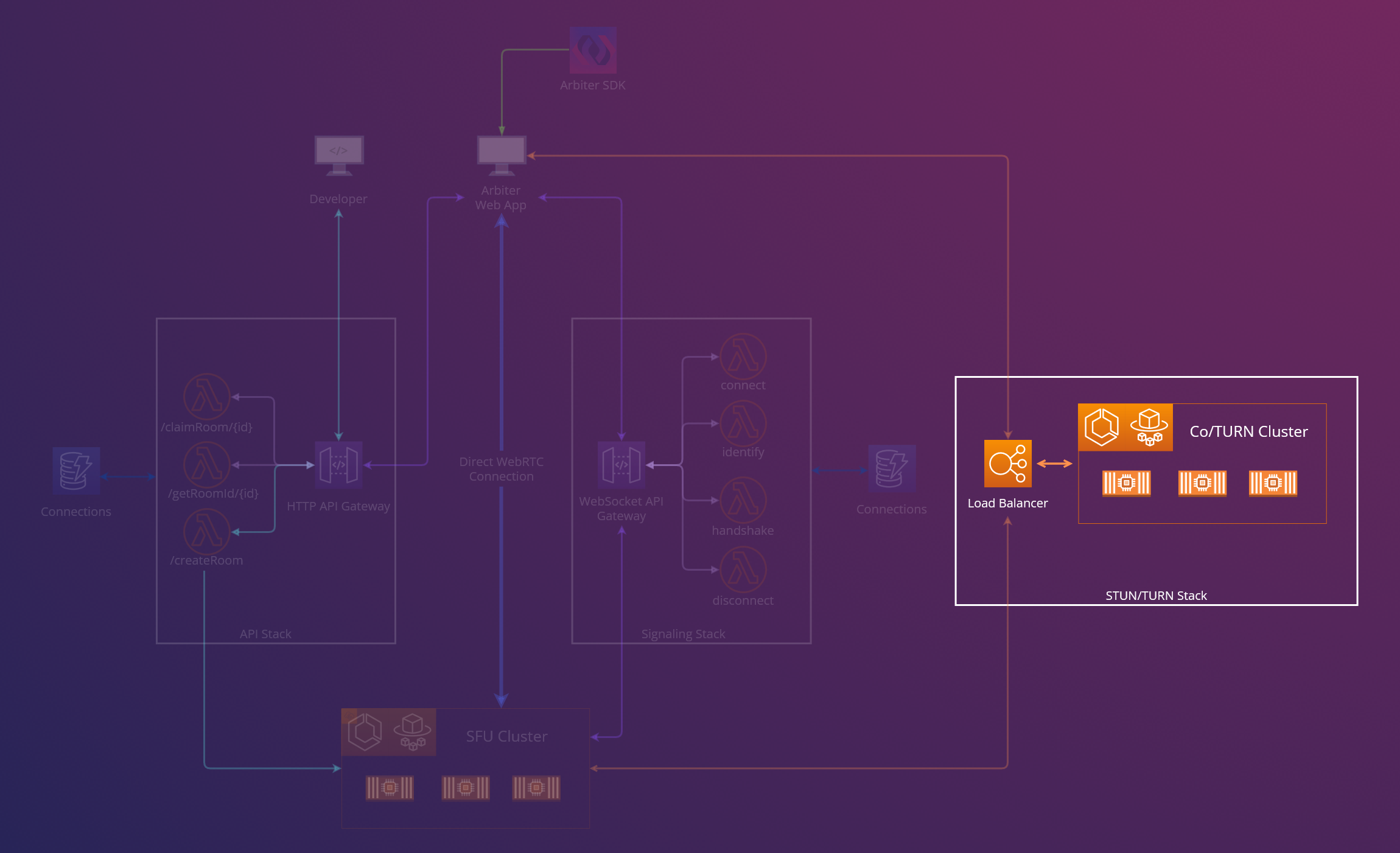

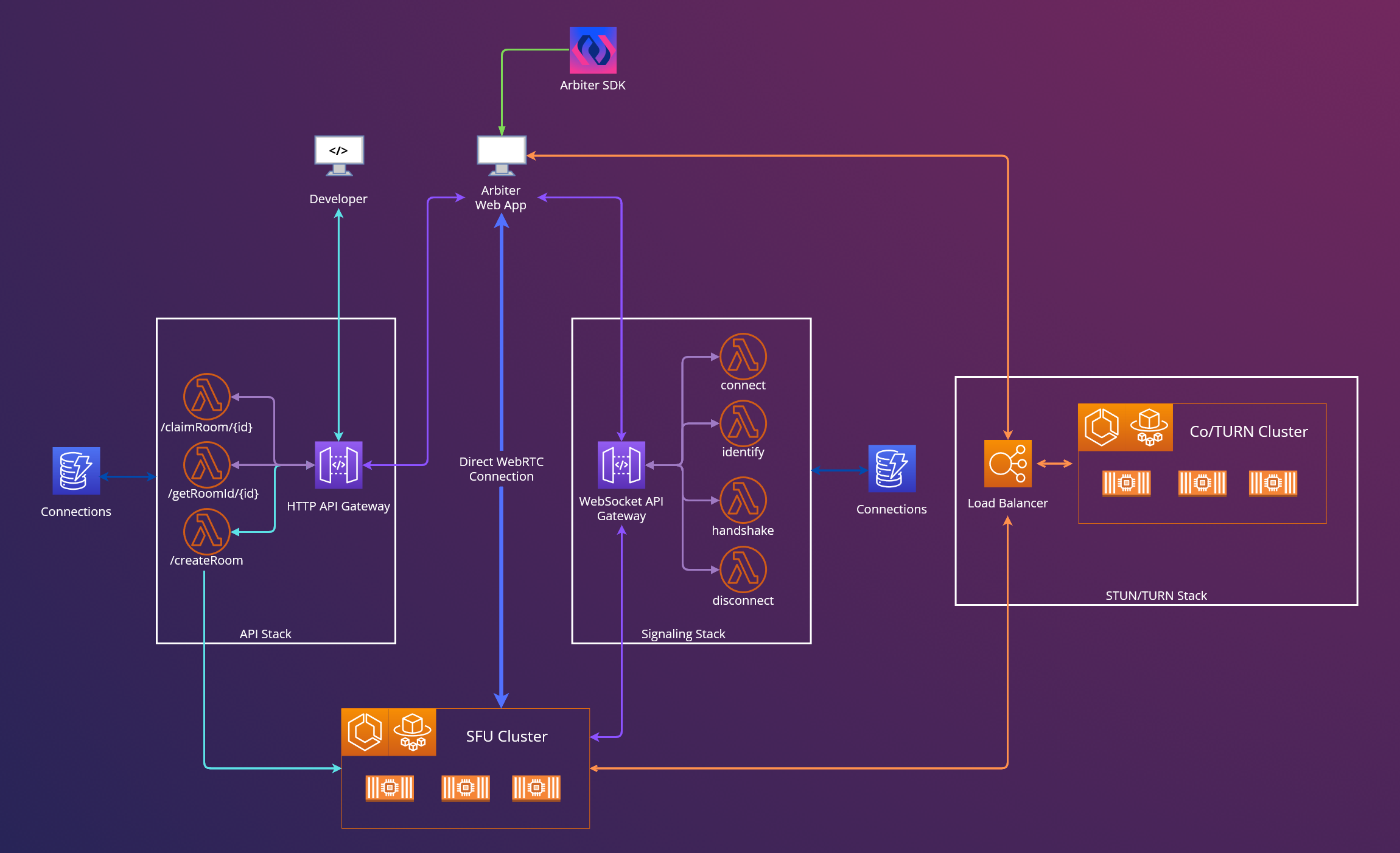

Building upon the insights garnered from our prototype, we undertook a comprehensive redesign of our system architecture. This redesign was specifically aimed at addressing the challenges of deploying and scaling the EC2 server components that we identified during our second prototype phase, so that Arbiter met its design goals. After Arbiter’s redesign, the architecture now consists of five key components, each serving a distinct function:

- SFU cluster

- STUN/TURN cluster

- Signaling Websocket API Gateway

- The HTTP API Gateway

- React Software Development Kit (SDK)

In the following section, we will examine each piece of Arbiter’s architecture in detail. This analysis aims to explain the specific purpose and function of each element, and to demonstrate how they collectively address the challenges encountered in earlier iterations of the project.

SFU

To resolve the scaling challenge associated with increasing the number of user-accessible rooms, we opted to containerize the SFU instances and deploy them via AWS Elastic Container Service (ECS) on AWS Fargate. Containerization, which facilitates the running of applications within an emulated application layer of an operating system, presented several critical benefits for our specific use case. First, the process of creating and decommissioning containers is quick and inexpensive, particularly when contrasted with the deployment and configuration of a complete EC2 instance for a single application. Second, a single ECS cluster is capable of managing up to 5,000 containers, thereby enabling the accommodation of numerous rooms without additional configuration. Third, Fargate manages both the underlying hardware and system on which the containers operate, including the management of the containers themselves. This approach inherently automates hardware and software monitoring, significantly reducing the workload for developers utilizing Arbiter.

STUN/TURN

Addressing the scalability of STUN/TURN servers was a critical challenge, driven by the potential for user overload on a single server and the necessity for TURN to relay media streams. Consequently, we opted for a strategy akin to our approach for scaling the SFU, utilizing ECS on Fargate. However, the communication dynamics with STUN/TURN servers differs significantly from those of the SFU, necessitating a different architectural approach. Contrary to the SFU that coordinates its communication with peers through the signaling stack, STUN/TURN servers directly interface with clients through the browser. This requires that all clients have access to the public IP address of a STUN/TURN server to facilitate WebRTC-based connections. We accomplished this through the implementation of a Network Load Balancer, which efficiently routes requests to STUN/TURN instances in the ECS cluster.

While building the STUN/TURN stack, a significant, unexpected challenge in scaling the stack was maintaining consistency in client-server communication. Specifically, when a client utilizes a STUN/TURN server for tasks like discovering their public IP address or stream forwarding, it’s imperative to maintain continuous communication with the same server instance. This necessity arises from the iterative process of discovering ICE candidates and the potential need to revert to a relay, which is essentially a continuous dialogue with the server.

To draw an analogy, consider the process akin to negotiating a car’s price. If, mid-negotiation, the original salesperson were to leave, forcing you to restart negotiations with a new, uninformed salesperson, the process would become inefficient, repetitive, and unlikely to reach a conclusion.

We encountered this issue initially when employing a network load balancer for our STUN/TURN containers. A client connected to a STUN/TURN server instance must sustain that specific connection consistently. This requirement is particularly critical when using TURN for stream data relay, as it necessitates continuous data forwarding to the same server instance.

To address this, we implemented sticky sessions in our load balancer, establishing a reliable and predictable communication pattern with the STUN/TURN servers, thereby ensuring consistent client-server interactions.

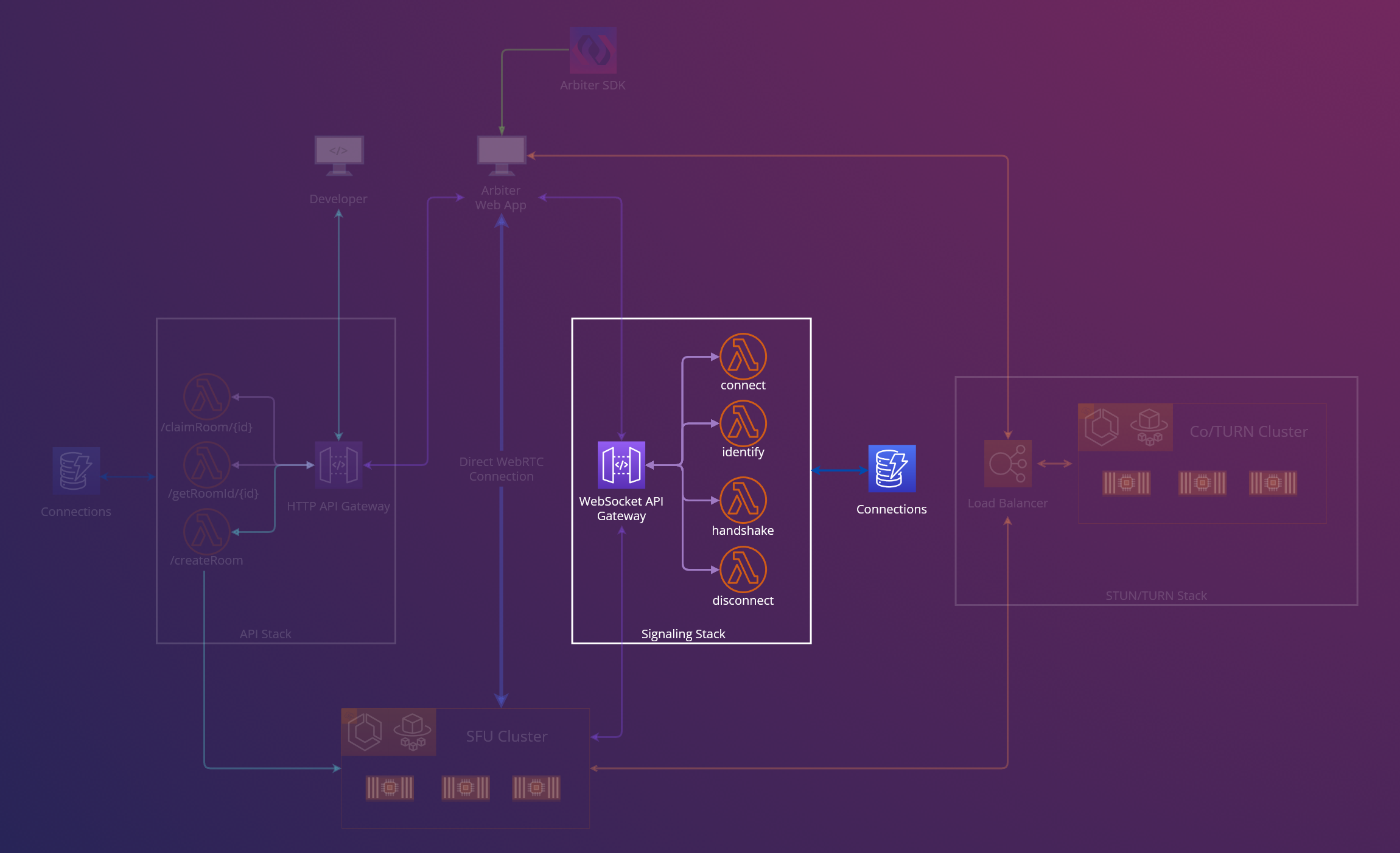

Signaling WebSocket Gateway

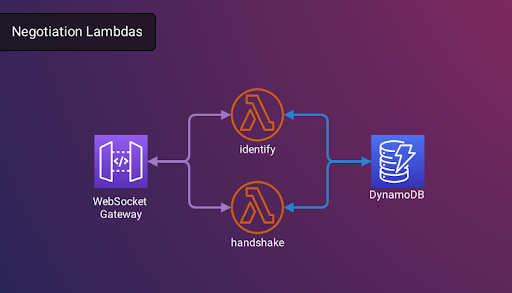

Although containerization of our existing signaling server was a viable option, it failed to resolve the critical issues of unnecessary costs and excessive uptime identified during our prototyping phase. The fundamental requirements for the signaling component were its operation through WebSockets and its perpetual availability. AWS’s WebSocket Gateway met these criteria; however, integrating it necessitated substantial refactoring of our existing application code. Importantly, this approach diverged from our previous solution, where our Express server managed the state of our application. Given the stateless nature of AWS WebSocket Gateways, it became imperative to utilize a database for storing room and session information.

To address this, we implemented AWS Lambda functions in conjunction with DynamoDB, handling signaling processes akin to those managed by our original Express server. Similar to the WebSocket Gateway, Lambda functions are stateless and require a persistent data source to accurately route messages. These functions are also scalable, dynamically adjusting to the volume of incoming requests, thus effectively addressing the scalability concerns of our signaling architecture. Despite initial apprehensions regarding potential latency issues and their impact on client application responsiveness, our practical usage and testing did not substantiate these concerns.

Arbiter’s WebSocket Gateway facilitates signaling through two distinct signals: identify and handshake. The ‘identify’ signal determines the nature of the connection (be it SFU or client) and updates the database for stateful connection management. The ‘handshake’ signal enables the exchange of various WebRTC-related signals between an SFU and a client, crucial for:

- Establishing a WebRTC connection

- Exchanging ICE candidates

- Transmitting Session Description Protocols (SDPs)

- Adding data channels

HTTP API Gateway

In the initial design of our prototype, the responsibility for creating and assigning rooms was delegated to the signaling server. However, the required refactoring of the signaling server necessitated the introduction of a new component to manage user authentication and room allocation. Similarly to a WebSocket Gateway, an AWS HTTP API Gateway functions as a stateless mechanism, facilitating on-demand communication via Lambda functions. The primary operations of the HTTP API Gateway, specifically the assignment and creation of rooms, occur less frequently compared to those of the WebSocket gateway, making it an ideal candidate for a stateless API Gateway. The fundamental responsibilities of the HTTP API Gateway include:

- Verifying the existence of a room associated with a specific URL

- Allocating an available SFU to users requesting room access

- Generating new rooms to replace those that are occupied

The HTTP API Gateway executes these tasks through three lambda functions, which interact with the same DynamoDB utilized by the signaling stack. This setup ensures seamless integration and coordination between the two APIs, thereby maintaining the room functionality established in the prototype.

React SDK

In our final development phase, we transitioned from hosting a standalone React application to establishing a React-component SDK. The SDK’s modular design is tailored to meet Arbiter’s primary use case: seamless integration into existing applications. Given Arbiter’s stateless architecture, the only requirements for the client application are a page’s URL route in combination with the addresses of the signaling stack, the HTTP API, and the STUN/TURN stack. Integrating these URL endpoints into a React application, users can effortlessly integrate the full suite of Arbiter’s functionalities into their applications with a single component addition. This method not only simplifies the integration process but also confers the advantage of enabling us to update the Arbiter front-end independently, obviating the need for any modifications on the user’s end.

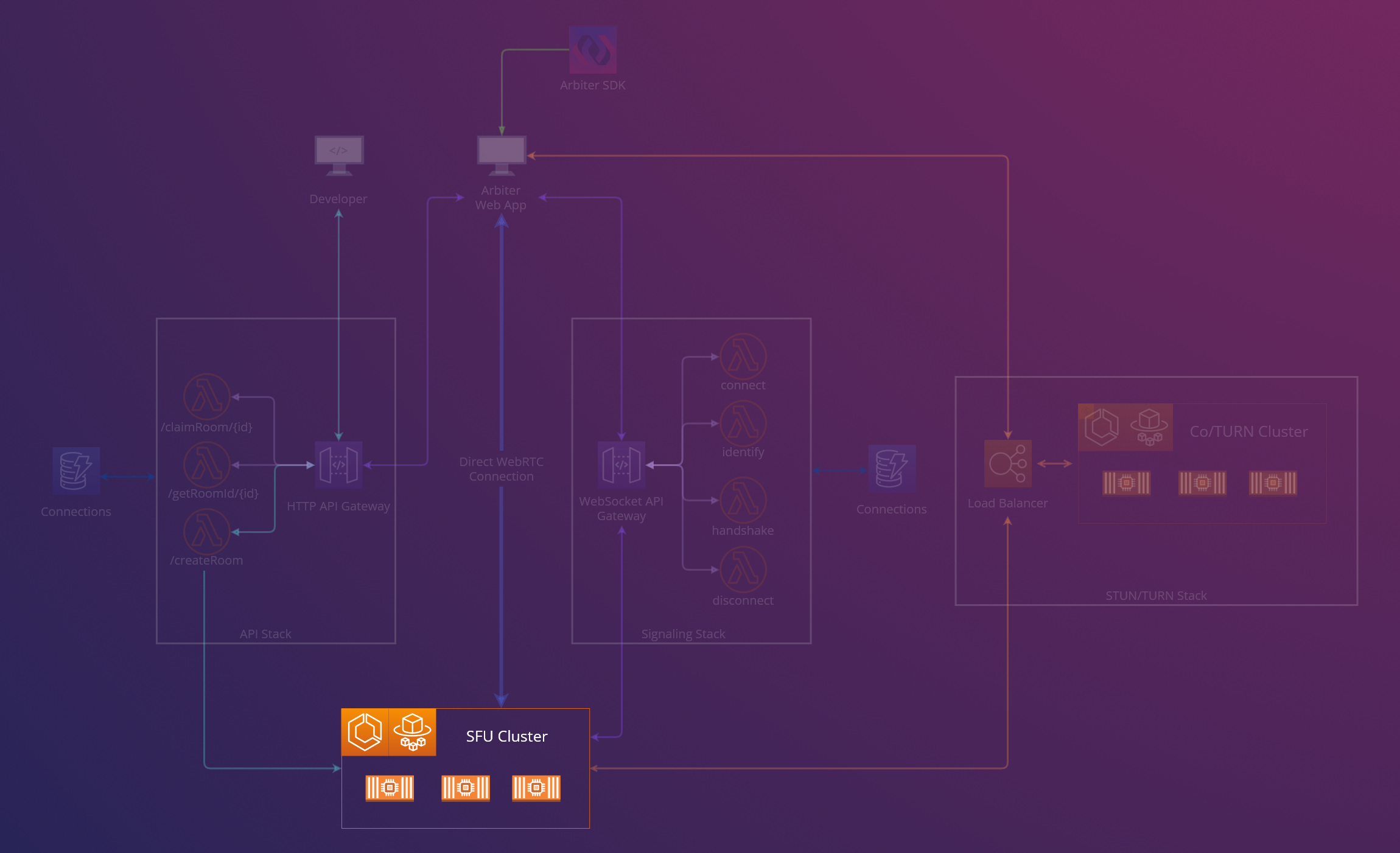

Putting it All Together

Together, these pieces make up Arbiter, which facilitates room-based conferencing to meet demand. Each component works together to reduce the complexity of implementing video conferencing so that a development team can focus on building their application.

Walking through this diagram, the general flow of events for a user joining a call is:

- When the React application first interfaces with the HTTP API Gateway, it will attempt to find a room by first checking if a room exists. If a room exists for that route, the API will return the ID of the relevant SFU container.

- If a room does not exist for this route, the React application then calls the API, which will provide it with the ID of an existing SFU server container.

- When a room is claimed, the API will instantiate a new SFU container instance using another route so that a room is available for another route.

- After having the ID of an SFU, the React application can use an available CoTURN container from the CoTURN ECS cluster’s load balancer so that it can generate ICE candidates.

- The React application then can connect to the Signaling Websocket Gateway with its SFU container ID and ICE candidates to begin the negotiation process with the relevant SFU container.

- Finally, the client can instantiate a new WebRTC connection with the specific SFU container that corresponds to that room in the SFU Cluster. Each user connecting to the same room will connect to the same SFU container, allowing users to hold a conference on the application.

In short Arbiter adeptly handles the intricacies involved in the creation and scaling of rooms to cater to an application's video conferencing requirements. This aligns with our primary goals of providing near real-time audio and video streaming capabilities, supporting multi-user calls across numerous rooms, enabling seamless integration with pre-existing applications, and ensuring simplified self-hosting. Consequently, for development teams employing Arbiter, the integration of video conferencing is streamlined to a simple incorporation of the React SDK within their existing application framework.

Further Work

Although Arbiter provides the functionality to address the problem we initially identified, there are several areas in which Arbiter could be improved. Some of the features we would like to add in the future include:

- Pagination of user media in a large call to improve the scalability of calls.

- Dynamic bitrate limiting of user media streams to accommodate users with slower connections.

- An ingress/egress to allow users to share their screen or other media.

- A more robust SDK that allows users more choices and customization with the appearance and features of their application.

Thank you for reading and enjoy using Arbiter!

References

Footnotes

-

Video Streaming Protocols What Are They & How to Choose The Best One ↩

-

WebRTC Encryption and Security: Everything You Need to Know ↩

-

UDP: Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) Request for Comments: 768 ↩

-

High Performance Browser Networking; establishing a peer to peer connection ↩

-

SDP: Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) Request for Comments: 4566 ↩

-

STUN: Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) Request for Comments: 8489 ↩

-

TURN: Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) Request for Comments: 8656 ↩

-

ICE: Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) Request for Comments: 5245 ↩

-

The multiple faces of WebRTC N-peer calling: Mesh, MCU and SFU ↩

-

AWS Fargate vs EC2 Pricing Comparison: Who Wins the Pricing War? ↩